JD Lock

Lieutenant Colonel, US Army (Retired), MS, PMP, LSSMBB

Future Force Reconnaissance Platoon Configuration

Proposed Changes to the FCS O&O Plan for the Combined Arms Battalion’s Reconnaissance Platoon

Lieutenant Colonel J.D. Lock, US Army (Retired)

February 2006

Note: While written a few years back and the FCS -Future Combat System/Future Force - concept has been what we call 'OBE' - Overcome by events -of Iran, Afghanistan and the cancelation of FCS, the ongoing changes as a result of incorporated advance technologies still applies...even moreso today than they did in 2006 given the overwhelming development and acquisition of C4ISR related systems.

The United States Army’s core effort to ensure conventional military supremacy on land, the Future Combat System (FCS), envisions an ensemble of manned and unmanned combat systems that are designed to be strategically responsive and dominant within the full operational spectrum of conflict. Fundamental to that dominance is the ability to incorporate and to exploit information dominance by developing a relevant common operating picture (COP) that enhances the force’s battlespace situational understanding.

Critical to the development of this COP at the tactical level is the Reconnaissance Platoon of the FCS Combined Arms Battalion (CAB). Unfortunately, as currently configured in the proposed FCS Operations & Organization Plan (O&O) force structure, the CAB’s Reconnaissance Troop reconnaissance platoons, as planned, will lack the capability to develop that relevant COP, thus seriously impacting the CAB’s ability to leverage its proposed advanced technologies in support of the close-in fight.

BACKGROUND: Under the FCS equipped Unit of Action (UA) [now redesignated as the Brigade Combat Team (BCT)] O&O, the Reconnaissance Platoon’s structure (Figure 1) calls for three FCS Reconnaissance & Surveillance (R&SV) type vehicles and a total of 18 soldiers:

Figure 3-21, Page 3-31

Change 3 to TRADOC Pam 525-3-90 FCS Equipped UA O&O 15 December 2004

Figure 1

The O&O also directs the following in regards to the FCS Reconnaissance Troop mission:

Gain information superiority over the enemy through active R&S operations. Gain and maintain contact with enemy forces, develop the situation and enable the SA of the supported commander. Provide security through R&S.

The Reconnaissance Troop tasks are—

• Conduct R&S (mounted and dismounted) operations to develop battlefield mobility and emplace observation.

• Perform R&S on a minimum of three routes or nine NAIs [Named Area of Interest] (using manned and unmanned sensor capabilities). Performs

limited communications relay with CL III UAV [Class III Unmanned Arial Vehicle] and ARVs [Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle] as required.

• Conduct the traditional “Sapper” tasks, conducts limited breaching operations, locate minefields, categorize enemy bridges and fortified structures.

• Provides sensor data and sensor data relay from its organic sensors and limited communications relay capability. Provide sensor data from its

organic sensors, both manned and unmanned, to produce combat information into the COP. Performs limited communications relay with Class

III UAV and ARVs as required.

• Perform target acquisition tasks and calls for effects as part of normal operations.

Reconnaissance Troop Mission, Pg 3-31

Change 3 to TRADOC Pam 525-3-90 FCS Equipped UA O&O, 15 December 2004

DISCUSSION: Chapter 11 of FM 3-0 Operations [which supersedes FM 100-5] describes Reconnaissance Operations as follows:

In some situations, the firepower, flexibility, survivability, and mobility of reconnaissance assets allow them to collect information where other assets cannot. Reconnaissance units obtain information on adversary and potential enemy forces as well as on the characteristics of a particular area.

Reconnaissance missions normally precede all operations and begin as early as the situation, political direction, and rules of engagement permit (see FM 5-0). They continue aggressively throughout the operation. Reconnaissance can locate mobile enemy C2 assets, such as command posts, communication nodes, and satellite terminals for neutralization, attack, or destruction. Commanders at all echelons incorporate reconnaissance into the conduct of Operations.

Given such tactical and operational level reconnaissance directives, the question then becomes: Can the Reconnaissance Platoon force structure as proposed by the FCS O&O meet the requirements set forth by FM 3-0 and the FCS O&O?

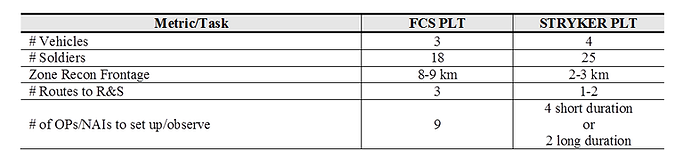

In an attempt to establish a reconnaissance baseline reflective of current doctrine, we can contrast the FCS reconnaissance Troop mission task requirements with the reconnaissance tasks of an equivalent Stryker reconnaissance platoon. Taking an extract from Army FM 3-20.971 Reconnaissance Troop: Recce Troop and Brigade Reconnaissance Troop (2Dec2002) and Army FM 3-20.98 Reconnaissance Platoon (2Dec2002), we can create the following Metric/Task matrix (Table 1):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1

At first glance, there appears to be some glaring resources vs. capabilities deficiencies within the FCS Recon platoon as designed within the O&O. But a simple matrix is not enough to validate this hypothesis. Empirical data and observations are needed to support such claims.

EXPERIMENT/DEMONSTRATION: In support of the Future Combat Systems (FCS) ‘spin out’ experiments for integration of advanced technologies, the Communications and Electronics Research and Development Engineering Center (CERDEC) conducts an annual ‘On-The-Move’ (OTM) Testbed field experiment at Fort Dix, New Jersey. With the assistance of National Guard infantrymen who execute the operational assessment, this testbed designs an experiment that integrates the latest Command and Control, Communications, Computer, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) technologies available for evaluation against an Opposing Force (OPFOR) in a field environment.

For the purpose of this year’s 2005 experiment, those advanced technologies were:

-

FBCB2: Force XXI Battle Command, Brigade & Below with upgraded software

-

SRW: Soldier Radio Waveform

-

UAVs: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

-

TACMAV (Tactical Micro Aerial Vehicle)

-

Raven (Class I surrogate)

-

Buster (Class I)

-

-

SUGV: Small Unmanned Ground Vehicle

-

ToughBot

-

LynchBot

-

-

C2V/R&SV: Command & Control/Reconnaissance & Surveillance Vehicle (surrogate)

-

ARV-R: Armored Robotic Vehicle – Reconnaissance (surrogate)

Given that these spin out experiments are in support of the FCS, the FY05 Testbed experiment’s experimental force structure was designed around the reconnaissance platoon of the CAB Reconnaissance Troop. While there were a number of experimental evaluation objectives, in particular the advanced technologies ‘value added’ to mission accomplishment, this exercise also provided an opportunity to evaluate the viability of the future force task organization.

As it so happened, it is this author’s contention that the experiment clearly demonstrated that the proposed FCS Operations & Organization Plan (O&O) force structure for the Combined Arms Battalion’s (CAB) Reconnaissance Troop reconnaissance platoons will most likely fail to accomplish their assigned missions the majority of the time as a result of vehicle and manning limitations.

Manned Vehicles: A three vehicle platoon, as currently proposed for the FCS organization, hinders force protection for it provides no flexibility to operate in two separately secure groups. The ‘wingman’ or ‘buddy’ concept is an integral concept in combat operations and, to operate otherwise, independent of any mutual support, is generally against US Army doctrine. Thus, inherent in a three vehicle platoon configuration, is the implied task that all three vehicles will have to stay together at all times, whether stationary or on the move. To do otherwise, would require a single vehicle to move independently, on its own. Consequently, in the event contact is made with enemy forces, there would be no ‘bounding overwatch’ element—the doctrinal movement technique required under such circumstances—available to provide supporting fires. This risk is too great a burden to intentionally or routinely place on an American Soldier.

Furthermore, reconnaissance is not all about stealth and surveillance; there are also times reconnaissance missions require occupation of an area by force or reconnaissance by fire (IAW FM 3-0). Furthermore, even when the mission calls for stealth and surveillance, there are instances when stealth and surveillance fail and the recon element comes under enemy fire. This inability to create two maneuver elements without taking extensive risk hinders and limits the reconnaissance platoon leader’s tactical options and could ultimately not only endanger the success of the mission but also the lives of the platoon members. The fact that an FCS BCT reconnaissance platoon will ultimately have a fourth, heavily armed, unmanned ARV-RSTA is irrelevant given that the robotic operator for that ARV-RSTA vehicle will most likely be in the ‘wingman’ vehicle. When that wingman vehicle comes under fire, who’s to operate the ARV?

There is an additional operational rationale for expanding to four manned vehicles beyond that of force protection. There are two primary platoon level unmanned vehicles available to the platoon leader—a Class I UAV and the ARV-R. Both unmanned vehicles (UV) cannot be operated by the same operator simultaneously for each has a significantly different command & control (C2) operational ‘tether’ that requires the focused attention of the operator. Given that the UAV will be flying high with a relatively unobstructed link, its controller has the ability to control the UV from greater distances than the controller linked to the ARV-R, whose ability to remotely control that UV will be seriously hampered by terrain and, thus, would require the Operator Control Unit (OCU) to be within close proximity of the UV. This operational constraint would require the platoon’s manned vehicles to operate in a split configuration, which, again, cannot be safely executed in a three C2V/R&SV configuration.

Personnel: A comparison of the FCS and Stryker reconnaissance platoons’ manned resources and their corresponding tasks with those resources—combined with the actual field experiment observations—leaves one seriously doubting that an FCS based reconnaissance platoon will be able to accomplish two to three times the operational tasks that a Stryker reconnaissance platoon currently performs with 1/3 more manning. FCS technology does not provide enough leverage for so small a force to successfully maintain force protection and accomplish just a few of those tasks, much less all of them. The O&O concept does not sync with the reality of what’s on the ground, even with technology that may be on hand years from now.

Mounted, the Recon Platoon, as designed, meets the minimum requirements, but just barely. Dismounted, though, the force is sorely inadequate to the tasks they are doctrinally charged to execute. In a dismounted configuration, the dismounted force can consist of no less than three members for two specific reasons: 1) Should one team member become KIA or WIA, it will take at least one other team member to recover the KIA/WIA soldier and a second team member to provide security as they withdrawal 2) The employment of a team SUGV will take one operator, one security element whose only primary function is to stay alert to his surrounding environment and the team leader to focus on C2 through his FBCB2 Tablet and relay SUGV ISR to the platoon leader. The addition of a fourth C2V/R&SV vehicle (as discussed in the Manned Vehicles paragraph) without a corresponding primary leadership or functional requirement would allow for a fourth team member to be deployed with the dismounted team—or remain with the vehicle to provide additional local security. Should the fourth team member dismount, this provides the platoon leader with one larger, four man team that can be employed on any mission he deems his platoon’s ‘main effort.’ Thus, with this configuration ten platoon members could be committed to a dismounted force.

That said regarding the dismounts, the remaining platoon members with the C2V/R&SV vehicles, as designed, are also inadequate to the task. For the reasons stated before, we will assume a construct of four C2V/R&SV vehicles. Each vehicle would require dedicated drivers and VCs (vehicle commanders). Drivers must remain with their vehicles at all times, though an ‘additional duty’ of the VC could be to also serve as dismounted local security while assembled at stationary objective rally points (ORP). Primary leaders and functional personnel—the platoon leader, platoon sergeant and Robotics NCOs—cannot perform both VC and C2/ISR related duties—especially anything force protection related. Hence, the four vehicles would require eight dedicated personnel to operate and to secure the vehicles.

As discussed in the Manned Vehicles paragraph, the operation of the Class I UAVs and the Armed Robotic Vehicle-Reconnaissance (ARV-R), as currently designed, appear to be under the control of a single Robotics NCO. If this is the case, two major technological advances are seriously handicapped by the fact that only one can be used at a time for one NCO will not be able to both fly an UAV and maneuver/fight an ARV-R simultaneously.

Furthermore, as currently designed, the plan calls for the Robotics NCO to be located in his own vehicle which impacts not only the platoon leader’s influence of where to fly and of what to ‘chip’ (imagery), but also delays the timeliness of the flow of such ISR information. The most significant ISR asset the platoon leader has is the UAV for it provides the most maneuverable and accessible ‘picture’ of the battlefield. It is also, most likely, the primary tool for target acquisition which will lead to ‘Calls for Fire’ and ultimate Battle Damage Assessments (BDA). Consequently, the Robotics NCO is the equivalent of a company level ‘FiST’—Fire Support Team—and, as such, should be in the platoon leader’s ‘hip pocket,’ where the platoon leader can quickly reach out and ‘touch’ him to immediately acquire and transfer imagery in a seamless and timely manner. The second Robotics NCO would serve out of the fourth C2V/R&SV. As proposed in the Manned Vehicles paragraph, this provides the platoon leader the flexibility to allow a two vehicle section—under the control of the Platoon Sergeant—to move forward to maintain R&SV control while allowing him to remain stationary at another location to maintain positive control of his UAVs overhead with another vehicle providing local security.

OBSERVATIONS/CONCLUSION: The Reconnaissance Platoon must not only be designed to meet the most demanding manpower intensive scenario they will most likely be faced with—dismounted teams and roving ORPs—but it must also be provided enough internal combat power—especially given the fact that they generally operate independently, forward of friendly lines—to protect itself. As currently designed, the FCS O&O for the CAB’s Reconnaissance Troop’s recon platoons fails to meet these needs.

RECOMMENDATION(S): By doctrine, force protection and security requirements fundamentally imply that four manned vehicles are the minimum number of vehicles that should operate at any tactical combat platoon level. Furthermore, if an FCS reconnaissance platoon is to accomplish the specified and implied tasks identified in the O&O, it would need to be configured as such, as a minimum (Figure 2):

Figure 2